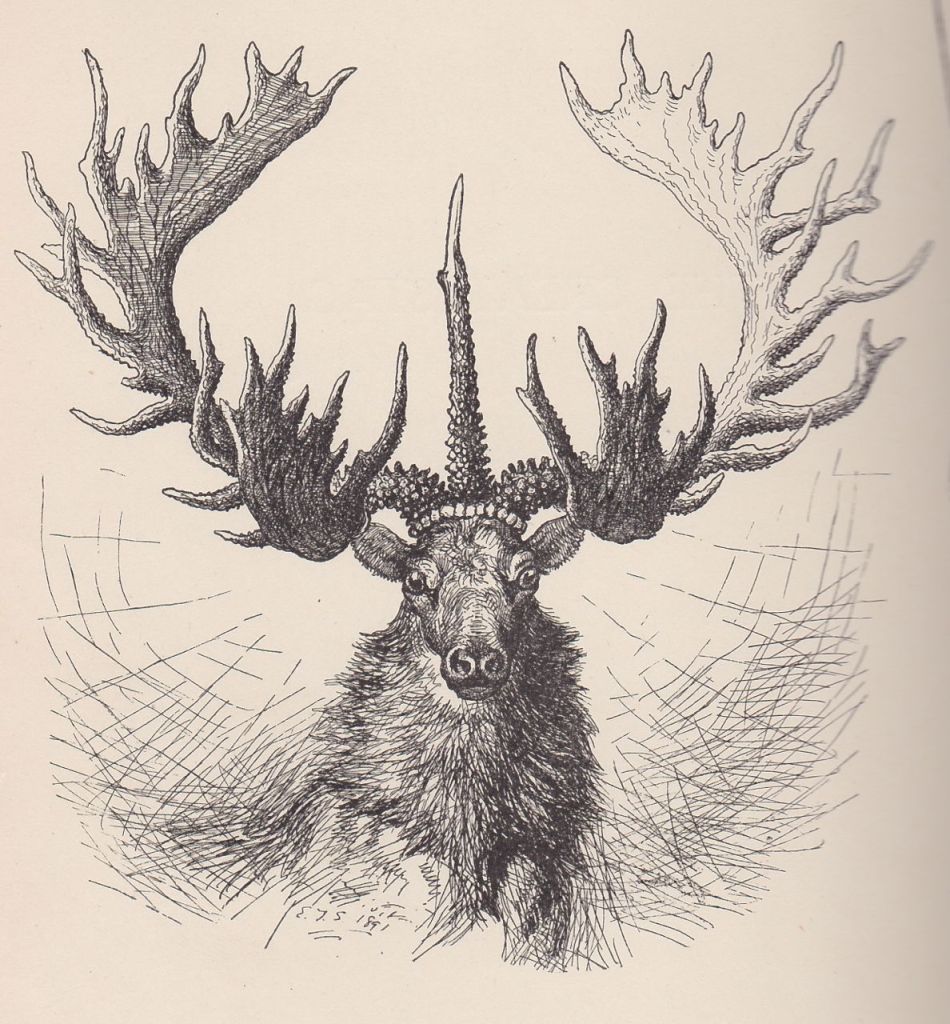

WE all know him well; his existence is established now as surely as that of the sea-serpent or the big fish that got off the hook — even better, for many of us have seen him in broad daylight and had a fair open view of his noble form. And what a creature he is, what a paragon of size and development! One observer, who had an exceptionally good look at him, counted twenty-seven tines on each antler. And such antlers! absolutely symmetrical and perfect, in every way befitting his immense stature and noble beauty. I am sure it cannot be that he shed them above once in twenty years, if at all. Another equally reliable historian asserts that this woodland Kraken has three antlers, the third a spike in the center. So far all is abundantly attested, but I must say that I place but little faith in that story of a chaplet of pearls about his brow; it is simply the knotted bead-like antler-burrs, white and polished, and glistening perhaps with the morning dew; while the crucifix in the middle, that has been reported, is nothing more than the spike-horn above referred to.

I expect to learn some day that he casts no shadow, for this I certainly know, that oftentimes he leaves no track behind him in the snow. His speed, too, is marvelous; it is as the wind. He seems — nay, he actually is — ubiquitous. Why! I first met him in the woods of Ontario; then, shortly afterward, I encountered his scornful gaze amid the sand-hills of Manitoba. I have heard for certain of his having been seen in the cane-brakes of Kentucky and amid the valleys of California. Even in England he was well known till quite lately, and bore the name of “The White Hart Royal,” and in Scotland he is still famous as “The Muckle Hart of Ben More.” Nay, more than all this, St. Hubert himself was blessed with a sight of the tricerate head, in the forests of Germany, and he, in fact, is responsible for that story of the central crucifix. The great Munchhausen, too, has much to say about this noblest of deer, “and what need have we of further witness?”

But it matters little where he dwells; no human hand has ever touched his glossy coat. He seems endowed with a charmed life; no bullet cast of lead can ever reach him. Of course a ball of silver might; I have never tried that, and I do not remember that any Croesus ever went about riddling innumerable bushes with costly projectiles in hopes of securing the Great Stag. I doubt, too, that he would have succeeded; indeed, I feel sure that no hunter armed with such infallible missiles will ever meet with St. Hubert’s Hart. He is too sagacious to allow it, or, if he did, he would not long remain in sight; he would simply show himself and snort and stamp — I know it, for I have watched him — then fade away, like the Cat in Wonderland, the scornful gaze being the last thing to vanish into thin air. He leaves a good track for a little while, but this, too, fades away completely. Once I followed it for miles, but it disappeared at last in a thickly grown bottom-land, and no doubt the phantom buck himself had vanished at the selfsame place. An Indian who was hunting with me thought otherwise, and persisted in circling off in another direction, so that we parted; but he was a fool, and when after two or three hours he came again to camp, bringing with him an ordinary buck, I could not but smile to see how completely he had been baffled.

It has never been decided even of what species he is; some testimony points one way and some in another. For my own part, I do not believe that he is a species at all, but a genus — genus Cervas; nothing more. One recent writer, however, claims that this was an elk, and was known for long in Pennsylvania as “The Lone Elk of the Sinnamahoning,” in which valley he was killed in 1867. But that, of course, is all nonsense. No, no! I know too much about him to believe any such tale. You cannot wreck the Flying Dutchman; he still will sail under great billowy clouds of canvas, till the last trump blows and the Kraken lashes all the sea to foam, and, belly upward, floats to show the end has come.

No, no! Still he roams and bounds from hill to hill, as I have seen and yet may see again — yea, even now do see in fancy’s eye along my glistening rifle-barrel. Again I see that glorious head against the sky, as often I did — more often in early days than now, for he appears most often to the tyro in the woods — see him give one great bound when cracks the ready rifle, and know from the miraculous way in which the unerring ball was turned aside that this was indeed the Mighty Stag again, the Spirit of the Race, and that no bullet cast of lead can ever graze his hide — and again he fades away.

Long may he roam and spurn the hill-tops with his flying feet and dash the dew-drops from the highest pine-tops as he clears the valley at a bound; long may he live and tempt a hail of harmless lead. But the rattle of repeaters is heard in every valley now; the wise are more and more often propounding that unfathomable riddle, “Where have all the Deer gone?” and when at length the last remainder of the common race is slain, I know too well that this, the immortal, too will die; that though he never can be touched by death, he yet will perish — perish like the last surviving Cambrian bard, not by the hand of man, but by a strange engulfment so complete that not a trace of him will e’er be seen again and but a fading memory of his ever having been.

The Great Stag by Ernest Thompson Seton first appeared in 1891, published by Forest & Stream. The drawing and article also appear in the book, Woodmyth & Fable by Seton published in 1903.

Happy Hunting! From the Master Woodsman Team

No intelligent comments yet. Please leave one of your own!