You are likely familiar with Leave No Trace (LNT), if not the organization, at least the concept it promotes in that there are set of principles to enjoy the outdoors responsibly while minimizing environmental impacts. Interestingly, the organization is very strict when it comes to the use of the copyrighted term, it’s logo, and their Seven Principals. Therefore, please take note this article is for educational purposes. That being said, The Seven Principles of LNT in short form are below, but I strongly encourage you to visit their webpage HERE for the details, as in this article, we will be discussing the impact LNT has had on outdoor living skills, especially woodcraft.

The Seven Principals of LNT

- Plan Ahead and Prepare

- Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces

- Dispose of Waste Properly

- Leave What You Find

- Minimize Campfire Impacts

- Respect Wildlife

- Be Considerate of Other Visitors

A Brief History of LNT…

Currently, LNT is a non-profit organization founded in 1994, but it was originally created by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) in the 1960s to address an increasing public land-use. By the 1980s it was a formal program emphasizing wilderness ethics, sustainable travel, and camping practices. In the early 1990s, the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) contributed “hands-on, science-based minimum impact education training for non-motorized recreational activities.” ALL THIS according to LNT’s history.

When I first read LNT was started by the Forest Service, the first thing I thought of was Smokey Bear. With a degree in Forest Resources & Conservation and being an experienced land manager, I am all too familiar with the USFS’s history of fire suppression. Decades of which had ecologically altered our nation’s forests for the worse, not to mention the additional consequences of more dangerous and expensive wildfires.

I am NOT suggesting anything of that magnitude from LNT ecologically. I am just pointing out a flaw in a previous USFS policy as I believe we have one in LNT. What? A government entity did something wrong? Hey, we all have our flaws! And for what it’s worth, the USFS has done some amazing research over many decades. These days, the fact they are getting any management done in the face of tough and changing political climates deserves some kudos! Unfortunately, I can’t say the same for LNT and what they have and continue to do in both outdoor and environmental education.

A Little More History

Let’s start from the beginning. From the article published by Environmental History.net, From Woodcraft to ‘Leave No Trace,’ by James Morton Turner (2002):

“…Between the 1800s and the 1930s, woodcraft formed a coherent recreation ethic, and an important precursor to the modern wilderness movement. For aspiring woodsmen, a selection of manuals promised to reveal the secrets of woodcraft. George Washington Sears penned the first of these, titled Woodcraft, in 1891. In these guidebooks, several characteristics distinguish the woodsman from the walkers and autocampers; his practice of woodcraft celebrated a working knowledge of nature; he exhibited strong misgivings for the abundance of consumer goods available to the outdoorsman. This dual concern – for leisure in the woods, and the consumer economy beyond – emerges as a central tension in woodcraft.

For the woodsman, the woods promised a working vacation. Surveying the table of contents of woodcraft guides such as Horace Kephart’s Camping and Woodcraft (1906), Edward Brecks’s The Way of the Woods (1908) or Elmer Krep’s Camp and Trail Methods (1910) reveals common chapters on essential wilderness know-how. In the outdoors, a woodsman judged himself by his skills in hunting, tanning furs, preserving game, building campfires, setting up shelters, and traveling though the forest. Summing it up, Kephart called woodcraft “the art of getting along well in the wilderness by utilizing nature’s storehouse.” In contrast to walking or autocamping literature, none of these handbooks sought to teach outdoorsmen how to pass through wilderness as a visitor. The real measure of a woodsman was in how skillfully he could recreate wilderness as his home.

Proficiency in woodcraft required an intimate, hands-on knowledge of the woods. These expectations are best set forth in the early Boy Scout manuals. An ax was the young scout’s most important tool. With it, the first edition of the The Official Handbook for Boys (1912) explained, the scout could furnish his entire wilderness camp. Ten straight branches could be assembled into a lean-to; and cut boughs served to thatch the roof. Two lean-tos facing one another made for an especially comfortable camp. In the kitchen, pot lifters, plates, and cups all could be fashioned from sticks and bark. Ernest Seton, in The Woodcraft Manual for Boys (1917), challenged the young woodsman to practice “hatchet cookery” and furnish his entire meal with his hatchet alone. Both the Boy Scout manuals and other woodcraft guides assumed that the skilled woodsman could identify trees (particularly those that burned most cleanly), knew the habits of animals (so he could kill them), and could identify a buffet of edible plants. The woodsman demonstrated his working knowledge of nature by using nature to his own ends.

Nothing troubled the woodsman more than being labeled a tenderfoot…”

Obviously a great deal happened between those days of old-style camping and now. Much of it is attributed to the varying definition of wilderness and its use. There was significant dialogue in late 1950s into the early 1970s on recreation vs. protection. Variables such as increased access through logging roads, increased automobile use, and organizations like the Sierra Club — at first encouraging hikers to get out (backpacking) and then questioning overuse (“saturation of wilderness”), added to the complexity (Turner, 2002).

The use debate was more than just public, it was within the Forest Service itself. With increased wilderness visitation (primarily backpackers) in the early 1960s, the Forest Service policies began to limit wilderness recreation thru permits and more. Regulations and increased disputes intensified after the Wilderness Act of 1964 was passed. The early 1970s saw a further tightening of regulations, and interestingly, an encouragement to visit the backcountry — this to spread out wilderness use as a form of protection, with the side benefit of discouraging many others.

Inevitably, groups wanting support (and protection) for wilderness meant supporting some sort of recreational access. Minimal impact camping was born. A new “modern” wilderness ethic based purely on aesthetics. There was no working knowledge (read understanding) of nature needed. All one had to know is that if nature was altered, it was wrong.

This ‘modern’ ethic spread across the land, spawning new literature chastising woodcraft while instructing how to “go light” and not “leaving a trace.” It also started a new era of gear where one could literally carry an entire camp on their back. Where once the woodcrafter was a participant in nature, the new backpacker was nothing more than a visitor to the wilderness.

Those 1970s movements led to the 1980s and now federally supported program Leave No Trace. When the minimal-impact wilderness ethic became solidified, it corresponded in time with lower wilderness visitation. A wilderness recreation industry would soon respond with appropriate gear and by further influencing policy and perception.

As shared earlier from LNT’s website on their history, the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) contributed “hands-on, science-based minimum impact education training for non-motorized recreational activities.” What LNT didn’t share on their website were companies like North Face, Gregory Mountain Products, and Mountain Safety Research, which also sell clothing, backpacks, and stoves, all financially supported Leave No Trace in the very beginning as well (Turner, 2002). And it’s no coincidence you see LNT’s logo branded all over a host of gear, maps, and more. Even the Boy Scouts jumped on the band wagon in 1998.

THE PROBLEMS WITH LNT

So what’s my knock on LNT, for one, (somewhat jokingly) they are too damn good at delivering a message! So good that today’s camper doesn’t seem to believe they are camping unless they have a backpack full of expensive ultralight gear (coincidentally from the same companies that support LNT financially to use their logo).

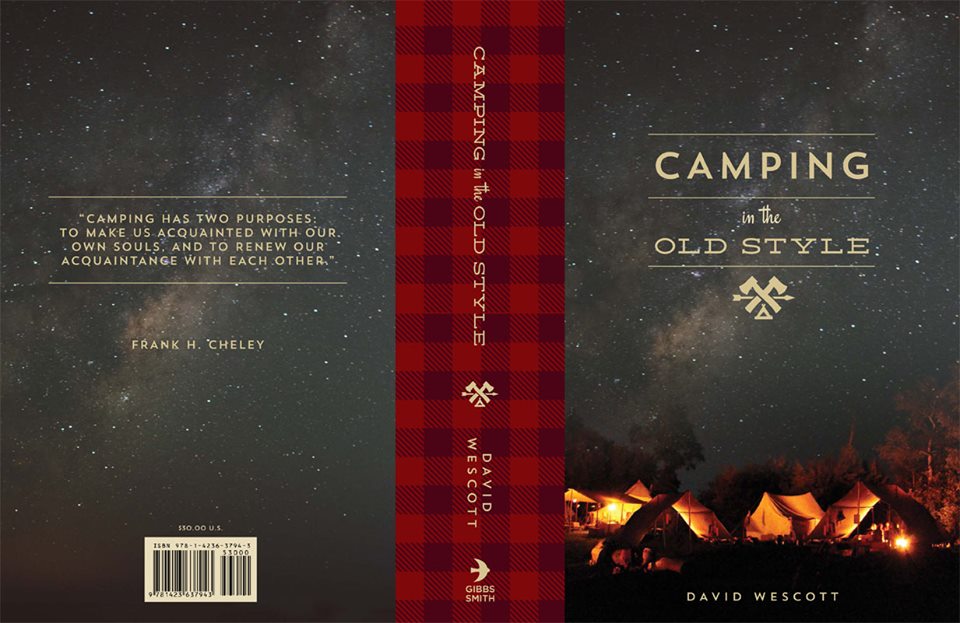

“Camping is what you do when you get to camp, and hiking is only one of many ways you may choose to get there.” Steve Watts and David Wescott articulate well in the December 2014 edition of American Frontiersman magazine. They also point out that “backpacking killed camping,” a word that didn’t even show up in outdoor literature until the 1940s.

Before this paradigm shift, backpacking was known as woodsrunning or tramping. Lightweight campers of the era (like today) were involved in the consumer-based economy of the outdoor industry — buying the ‘latest’ gear and gizmos from outfitters like Abercrombie and Fitch and others. But, they were also in touch with a long-standing tradition of modifying and hand-crafting their camp gear from dependable materials such as canvas, leather, brass, wood (poles and frames), and steel — a tradition that connected them more closely to the frontier skills of the not-too-distant past. Now we have the unfortunate model that backpacking is camping, driven by the LNT crowd.

Consequently, through promotion and those fore mentioned corporate relationships, the masses get (expensive) lightweight gear to fit the paradigm. This “new” gear is not only NOT near as efficient or dependable, in some respects, one could also argue it isn’t as environmentally ethical either. Or at the very least, LNT as a philosophy doesn’t think globally. Canvas vs. petroleum-based nylon for shelters. Wool vs. synthetic for clothing. And then there is the fire vs. stove argument.

Consequently, through promotion and those fore mentioned corporate relationships, the masses get (expensive) lightweight gear to fit the paradigm. This “new” gear is not only NOT near as efficient or dependable, in some respects, one could also argue it isn’t as environmentally ethical either. Or at the very least, LNT as a philosophy doesn’t think globally. Canvas vs. petroleum-based nylon for shelters. Wool vs. synthetic for clothing. And then there is the fire vs. stove argument.

From the LNT website on Principal 5: Minimize Campfire Impacts:

Fires vs. Stoves: The use of campfires, once a necessity for cooking and warmth, is steeped in history and tradition. Some people would not think of camping without a campfire. Campfire building is also an important skill for every camper. Yet, the natural appearance of many areas has been degraded by the overuse of fires and an increasing demand for firewood. The development of light weight efficient camp stoves has encouraged a shift away from the traditional fire. Stoves have be come essential equipment for minimum-impact camping. They are fast, flexible, and eliminate firewood availability as a concern in campsite selection. Stoves operate in almost any weather condition, and they Leave No Trace.

First off, sorry, but stoves do leave a trace. There is a hole somewhere in the earth where the rare earth elements were mined to build the stove and fuel container. There is a hole somewhere in the sky from the smokestack where they were manufactured. There is a pipe in the ground or under the ocean somewhere for the fuel to make the stove work and the boat and truck that brought them to you.

Am I saying don’t use stoves? NO! They have tremendous value in sensitive areas, above tree line, and more. But if you are going to expound on an environmental ethic, realize at the end of the day, there is only one wilderness and we all live in it. They skipped that part in the LNT training I went through.

CONSERVATION vs. PRESERVATION

“Once a necessity for cooking and warmth…“

“The development of light weight efficient camp stoves has encouraged a shift away from the traditional fire.“

“Leave what you find!” — the fourth principal of LNT.

Sometimes it feels like we are being preached to by a TV evangelist. Break one of the SEVEN COMMANDMENTS (I mean principals), and you will go to HELL! Everything must be PRESERVED. Well, preservation means to keep something exactly the same and Mother Nature doesn’t work that way.

Unlike the fossil fuels to run the stove, not to mention the materials to build it, firewood is a renewable resource! They make it sound the other way around. Shame on them! There is no such thing as leaving no trace. No matter what you do, you will be making a impact! Like the USFS did with fire suppression, in the long-run, LNT will end up hurting what they are trying to protect as it has made more than a generation of outsiders to the natural world.

Instead, we should learn about nature as a participant. By doing to so in a respectful manner with the proper guidance, you will find a conservation ethic allowing you to tread lightly across the landscape the way it was intended by our Creator.

“Conservation is a state of harmony between men and land.”

— Aldo Leopold, U.S. Conservationist and Forester

That being said, it is more than worth noting that the skilled and ethical woodsman can not only have a campfire (in most areas) of which you will see little to no trace, but the environment can be improved at the same time. If the energy put towards LNT was put towards sound outdoor knowledge versus what is deemed common sense purely through aesthetics, we’d all be better off.

Woodcraft isn’t the only loss… WILDERNESS SURVIVAL!

So go ahead and get out there in the backcountry, but don’t worry about the second most important outdoor skill, FIRE. Unfortunately, I have experienced firsthand the degradation of outdoor skills in BSA and elsewhere driven by LNT…

- Avoid using hatchets, saws, or breaking branches off standing or downed trees. Dead and down wood burns easily, is easy to collect and leaves less impact.

- Use small pieces of wood no larger than the diameter of an adult wrist that can be broken with your hands.

- Gather wood over a wide area away from camp. Use dry drift wood on rivers and sea shores.

The above is again from LNT. While it isn’t the responsibility of LNT to teach woodsmanship or modern survival skills, nonetheless, their principals have pushed away man’s relationship to nature and a valuable tool in fire.

I want to make a very important point about fire here from an educational standpoint; when it comes to your well being in a survival situation, you forget about LNT and do what you have to do. Fire maybe the only means available to make up for deficiencies in clothing and/or shelter, especially when compromised.

If through all your experience (and training), you haven’t learned the difference between a cooking fire and how to build a large warming fire, or even know how to light a fire with natural materials because you only know how to use a modern stove, I strongly suggest you learn if you spend time in the backcountry.

EVERYTHING IN MODERATION

Like most things in life, too much of a good thing will end up hurting you. I believe that is what has happened to the environmentally uneducated with LNT. Too much in too many places where man should instead be a part of the environment like he was intended, not just an observer who takes only pictures and leaves only footprints. You might as well as be an astronaut visiting the moon if that is all you do in nature.

We are NOT visitors here on Earth. This is our home and the home of our ancestors. How could one truly learn enough to form a conservation ethic to take care of environment when forcing themselves to constantly be an outsider?

Don’t get me wrong, in high traffic and sensitive areas I am a huge fan of treading lightly, even using a stove. Personally, I use a supercat stove I make from used diced chili cans with denatured alcohol for fuel, when and where it makes sense.

A SLOW COMEBACK

Woodcraft appears to be making a comeback, albeit very slowly. In my opinion, the reason for the slow return is four-fold.

- We have had roughly 50 years of Leave No Trace evangelism.

- There is an increasingly uneducated population that primarily lives in urban and suburban environments and elects an over-regulatory government.

- There are so many mediums of information these days, most of which are commercialized, those new to camping are overwhelmed, forced into a backpacking paradigm by that industry, and then guilted into LNT for its simple aesthetic approach which requires no ecological understanding.

- Much of today’s outdoor skill information is poorly taught and comes with very little context due to the presenter’s source of information, slack research, and minimal experience. While not intentional by the majority who want to share what they know, this loss of context unto itself is disappointing and dangerous as much of it passes as “wilderness survival.”

MASTER WOODSMEN OF YESTERYEAR

As mentioned earlier, it was folks like Seton, Beard, Kephart, White, Sears, Miller, Harding, Jaeger, Mason and others who first started to capture in literature many of the indigenous and frontier skills we now see coming back to the forefront. Perhaps, even unknowingly, people are looking to these original sources because they know in their hearts something is missing today.

Fortunately for us, there are folks out there promoting Woodcraft and Old Style Camping. Master Woodsmen of today such as Steve Watts and David Wescott are bringing to the forefront the skills, gear, philosophy and perhaps most importantly, spirit, from those Master Woodsmen of Yesteryear.

As a Master Woodsman reader, you and I are fortunate to call Watts and Wescott friends of the site. Their contributions here, and elsewhere, as well as the those we have listed in the schools and resource sections of this website are greatly appreciated. Hats off to the ACORN Patrol Classic Camping Demonstration Team and others promoting this outdoor knowledge too!

Our country has changed tremendously in the last century. Amazingly, the 117 year old Camp-Fire Club of America has never wavered. As they started over a 100 years ago at Ernest Thompson Seton’s Wyndygoul during the first Outing in 1910, to this day, many woodcraft and other other practical outdoor skills are kept alive through competitions held twice a year. They also do outreach into the BSA and continue conservation efforts as they have since their beginning.

What LNT has done to Woodcraft, in my mind, is an analogy of what society has done to self-reliance in general. Where the frontier and Depression era had spit out men and women of hard stock who knew how to take care of themselves and understood the land, our society in the last several generations has gone the other way. This article only offers a perspective, not an ethic. It is truly up to you to have an interest in the natural resources around you, learn the effects of your outdoor living practices, form a conservation ethic, and abide by those good practices.

Finally, to you the backpacker on the Appalachian Trail: The next time you are in the north Georgia mountains walking along that high Duncan Ridge section, if you smell woodsmoke coming up from one of the hollows, it’s probably me and my friends. Don’t worry though, there isn’t a trail to get to where we are, so no one will see our primitive camp. But if someone did catch us there, I know they would appreciate the campfire, the comfort of my wood frame bed, camp furniture, as well as some of the cooking accoutrements, all supplied by Mother Nature herself. The woods will look healthy where we are too, as Mother Nature has provided as she has told us. That suppressed tree and alike that were overcrowding its neighbors inviting pests and disease are now gone. In fact that is why we camped here, to participate in the environment in a positive way. And when the smoke clears and we have left, we will have burned most of what I have used to ash. What little charcoal is left is ground to a powder and spread into the forest as fertilizer. Where our fire once burned is now undetectable as we have scattered debris and leaf litter over it to prevent erosion. Yes, we took more than pictures, but we left something better, in the forest and in ourselves.

SUGGESTIONS

Attend WOODSMOKE – The International Classic Camping Symposium

Rexburg, ID. July 12 – 18, 2015

READ

Turner, James Morton. From Woodcraft to ‘Leave No Trace.’

Environmental History, 2002. PDF

Tyron, Don. Leave-A-Trace

Editorial, 2007. Blog

Camping in the Old Style by David Wescott, Coming July 1st

55 Responses to Leave No Trace killed Woodcraft… almost