Simply stating that Colonel Townsend Whelen (1877-1961) was just an outdoorsman is like saying that Babe Ruth was just a baseball player. According to the dust jacket flap of On Your Own in the Wilderness (Whelen and Angier), 1958, Whelen wrote his first outdoor magazine article in 1901 and afterward, his work appeared in outdoor magazines almost every month. In fact, one of the last pieces he wrote addressed the subject of this article and appeared in Sports Afield in June of 1961. Whelen was the camping editor of Sports Afield for twenty years, Director of Research and Development at Springfield Armory and commanding officer at Frankfort Arsenal. He was the developer of the Whelen rifle sling, the Whelen lean-to tent and the .35 Whelen rifle cartridge. During his lifetime, he wrote over twenty books and was known as Mr. Rifleman and as the Dean of American Outdoor Writers. To top it off, by all accounts, he was also a genuinely nice guy, with many friends.

Considering the above, and as strange as it may seem, when it comes to classic camping, I was always a little disappointed in the Whelen tent. Don’t get me wrong; it is a premier shelter, the pinnacle of lean-to development in fact, and I have weathered cold, sleet, snow and rain in them with ease over the years. My disappointment then, never stemmed from a lack of practicality, but from the fact that the Whelen tent was just too “new”. “It was designed by Townsend Whelen in 1925” (or 1926, depending on the source), so runs the conventional wisdom. This would have still put it in the Golden Age of camping (1880s-1930s), albeit toward the end of the era, but I was more interested in equipment and techniques from the middle period (turn of the century), so my Whelens were relegated to the shelf in favor of a wall tent and awning with all the accoutrements, except of course, when I needed to go classic and go light at the same time. Then the Whelen really shines as a practical, packable shelter for almost any kind of weather, provided one uses campcraft by picking the correct site and erects it so that the front opening is parallel to the wind. My old canvas one weighs in at 10 pounds, no more than a cheap nylon tent with fiberglass poles. A version could be sewn from Egyptian cotton sheeting that would weigh a mere six and one-half pounds. One of its few disadvantages is lack of privacy, but the Whelen is a wilderness tent, and this is not a concern in remote areas. I will not go into all of the details regarding the advantages and wonderful practicality of the Whelen tent, for Steve Watts has already done an excellent job of that elsewhere on this site (see In Praise of the Whelen Lean-To). Instead, I will focus on, what to me, is its fascinating origins.

The Simple Lean-To (Without Sides)

The simple lean-to is one of man’s oldest shelters, so there is really nothing new or innovative about it. They were used during the Golden Age by Beard, Kephart, Whelen and many others. Lean-tos were used extensively by hunters and trappers in the Yukon, British Columbia and Alaska at the turn of the century. Another of my camping heroes, Albert Faille (1887-1973) used one on his trips up the Liard and Nahanni Rivers in the Northwest Territories of Canada. Donald Wilder made an excellent film of one of these trips Faille took when he was 73 years old. His simple tarp lean-to with mosquito bar is evident in the film. It is an amazing documentary and is available here from the Canadian Film Board.

An Accidental Discovery

A few weeks ago, I was looking around for a good source for hand woven wool blankets at a reasonable price (not an easy thing to find). During one of my Internet searches, I noticed a link to a site featuring outdoor paintings by John Seerey-Lester.

Curious, I clicked on the site and scrolled down to the bottom. There was a painting of a Whelen tent which looked very strange to me. The tent looked just like one of my Whelens from tentsmiths.com, but the men inside were dressed in turn of the century clothing. I read the description at the bottom, which indicated that it had been painted after an account of one of naturalist Charles Sheldon’s 1906 bear hunts in Alaska. Now, I thought, this was very strange! How could Sheldon have been using a Whelen tent if it was not invented until the mid-1920s?

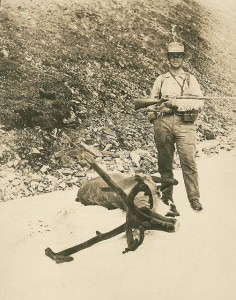

Charles. A. Sheldon with Caribou, circa 1910. Photo courtesy of Smithsonian Institution

Charles Alexander Sheldon (1867-1928) was a famous naturalist, and hunter. He hunted and camped extensively in British Columbia, the Yukon, Alaska, Nova Scotia, the United States and Mexico. He was the driving force behind the creation of Mount McKinley National Park (now Denali National Park) and spent an entire year at the foot of Denali in 1907-1908. Now, I was curious! If a Whelen-style tent existed this early in the twentieth century, I wanted to see a photograph of it! Subsequently, I discovered photographs at Alaska’s Digital Archives, a site where various institutions post their collections of digital images. The collection of original photographs found in the links (here and here) are from the Charles Sheldon Collection housed in the Shelburne Museum in Shelburne, Vermont.

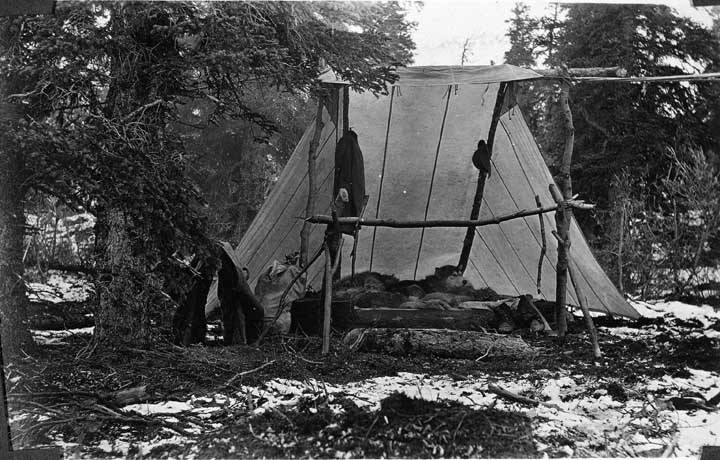

What I found was astonishing! Scrolling down to the bottom of the second page linked above, I found a photograph of what looked almost exactly like a Whelen tent, except perhaps taller and certainly narrower. It was made of what looked like balloon silk (Egyptian cotton). The photograph was dated May 23, 1908! How could this be? This was much earlier than 1926! I struggled for a plausible explanation. At first I thought perhaps Whelen might have invented an early version of the tent prior to 1908, but quickly realized this didn’t add up. The history of his travel, his writings and his experiences during the first decade of the twentieth century did not lead back to Alaska and the tent in the 1908 photograph.

Although Whelen took a notable trip to British Columbia in 1901, in 1908 when the photograph of Sheldon’s tent was taken, Whelen was busy settling into his career in the US Army. Furthermore, another Sheldon photograph on the Alaska’s Digital Archives site, dated June 30, 1906, shows an improvised tent rigged in a style similar to a Whelen tent. The 1906 photo, to be discussed further in this article, indicates that the Whelen style tent from the 1908 photo was created sometime between 1906 and 1908 to mimic this tarp arrangement.

That remarkable trip that Whelen took in 1901 in many ways defined the man and is chronicled in Whelen’s excellent piece “Red Letter Days in British Columbia.”

During this trip, Whelen and a guide named Bill Andrews spent over six months in uncharted territory, as he called it, between the Scumscum River and the Yukon. The only mention of a tent in this narrative was a small tent that formed one of their pack covers. In an article by David Petzal, which was uploaded to fieldandstream.com on June 6th, 2006, Whelen is speaking about the 1901 trip:

I gathered a little outfit which consisted of my .40/72 Winchester rifle, a .30/30 Winchester Model 94, the necessary ammunition, a light tarp 8×11 feet which I made, a pair of Army blankets and a poncho, a set of nested camp kettles, and practically nothing else. At Ashcroft (British Columbia) I bought a saddle horse for $25, two pack horses for $15 each, a stock saddle for $25, two sawbuck saddles for $5, and $25 worth of grub. An old prospector showed me how to pack the horses and throw the diamond hitch. The next morning I started out over the Telegraph Trail, bound for northern British Columbia.

If the Whelen lean-to had been invented prior to his 1901 trip, I think Whelen would have detailed it in his writings of the day, but instead he discusses a shelter cloth, apparently an 8′ X11′ tarp. Besides, at this juncture, he was just starting out in the region, so tent development was probably not at the top of his agenda.

According to Canoeing North Into the Unknown: A Record of River Travel, 1874 to 1974 by Bruce W. Hodgins and Gwyneth Hoyle, as early as 1904, Charles Sheldon and Frederick Courtney Selous (arguably the most famous British big game hunter who ever lived) were hunting in the area of the Macmillan River. Selous spent time in Alaska and the Yukon in 1904 and 1905. These trips are described in Selous’ excellent book, Recent Hunting Trips in British North America, 1907. Chapter ten of this book, titled “Hints on Equipment”, contains excellent information and is a valuable addition, considering how many nights Selous spent under canvas during his lifetime. On pages 386-387, Selous, in discussing tents capable of being carried by a person, states,

…wherever in North America trees are to be found, a light canvas waterproof sheet is preferable for camping purposes to a tent.” He goes on to explain how to erect it.

…a cross-pole is soon put up between two trees and a lean-to made with a few saplings over which the canvas sheet is stretched and brought well round at each end.

Selous then relates how a fire can be built in front to warm the tent. The ends being “brought well round” could have been a trick Selous picked up from Sheldon and his friends.

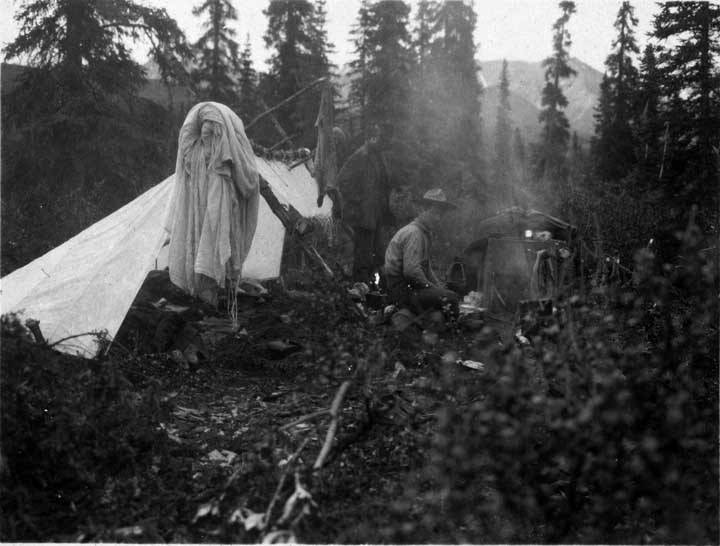

Sheldon’s lean-to tarp shelter with separate awning, 1906, photo courtesy of Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont

The photograph above, from the Charles Shelton Collection, Shelburne Museum, displayed on the Alaska’s Digital Archives site, offers a clue to the development of the Whelen lean-to. In the photograph, referenced earlier in this article and dated June 30, 1906, a tarpaulin shelter can be seen. Rather than being a simple lean-to, the ends of the tarp are bent around as Selous describes, and are pegged to the ground. A separate awning is attached to the front. In looking at the photo, one can see that the seams run from one end of the tarp to the other, making it obvious that it is a simple tarp shelter rather than any sort of tent with walls. Sheldon describes this arrangement in his book, The Wilderness of the Upper Yukon, 1911:

I had an open shelter, instead of a tent, with side wings so constructed that, when pegged to the ground, they inclined outward at an angle from the perpendicular, leaving extra space for storing provisions. A detachable strip of canvas, a foot wide, could be tied in front and sloped outward over inclined poles. This prevented rain from blowing in. No one who loves camp life can prefer a tent to a shelter, except in winter. The log fire which is always made before the shelter reflects warmth directly inside, so that one can sit at ease and in enjoyment in all but the coldest weather. A shelter is also more convenient to construct than a tent.

It sounds from the above description that he had refined the ends of the tarp since the 1906 photograph above, but had still not permanently attached an awning. Whelen and Angier in their superb book, On Your Own in the Wilderness, 1958, page 73, show a diagram of the tarp described above by Shelton. The diagram shows points on the end of the tarp and no awning. By 1908, as can be seen from the other Sheldon photograph, someone, presumably Sheldon, had a tent constructed from to mimic this tarp arrangement, presumably with awning attached. The two photographs from the Charles Sheldon collection referenced in this article indicate that the tent in the 1908 photograph was invented sometime between 1906 and 1908. As evidenced, it is very much like what we now know as a Whelen tent, even down to the ties under the awning to accommodate the clothes rod as described in Whelen and Angier’s On Your Own in the Wilderness.

This finished tent design was evidently very specific to that part of the world. None of the other writers of the day, such as Kephart, Miller, Cheley or anyone else were writing about it prior to the 1920’s, so it must have been a very localized design, exclusive to all but perhaps Sheldon himself. Sheldon would have certainly had the resources to commission such a tent. Already wealthy from his work and investments with the Chihuahua and Pacific Exploration Company, developers of Potasi, one of the richest silver and lead mines in Mexico, he was able to retire at 35 years of age to pursue his outdoor endeavors. His entire focus beyond this point was on being a naturalist and later, on getting a national park established. He may have simply needed a tent to suit his purposes which was more convenient to erect than a two-piece tarp, so at some point between 1906 and 1908. he probably paid someone to make it. His main objective was practicality, not to invent or market a new tent.

In On Your Own in the Wilderness, 1958, Whelen states, ” . . . after a lot of experience and experiment, I thought out what I called the Hunter’s Lean-to Tent. This I had made up by one of our leading tent makers who, incidently, has been marketing it since as the Whelen Lean-to.” the photo caption goes on to say that the original tent was first made in 1926, of “Abercrombie’s Green Waterproof Egyptian cotton”. It was used until 1955 and had seen at least 400 days of camping!

I puzzled over all of this for quite some time. I had always believed (and still do) that Whelen was a man of integrity who would not blatantly lie about such matters, and yet, I had concrete evidence that such a tent existed prior to 1926, with no evidence of a direct link prior to that time between Sheldon and Whelen. Still puzzled, I mentioned this to Chris Noble, the editor of this blog. Chris said, “wow . . . you’d better have your facts straight on that one”. I joked with Chris about not committing blasphemy, but it did not make me feel any better about my discoveries. I then discussed the matter with Steve Watts. Some time afterward, he remembered a long forgotten article from an October 1979 magazine called the Buckskin Report which he proceeded to fish out from his archives. The article references a piece Whelen wrote that appeared in the June 1961 issue of Sports Afield shortly before his death entitled “The Whelen Lean-To”. Whelen is quoted below:

. . . years ago the famous hunter and naturalist Charles Sheldon suggested to me how to improve the lean-to tent. Instead of leaving the lean-to open at the sides, or bringing the sides straight down, as in the Baker tent, the sides are splayed outward and forward so that the bottom end comes three feet forward and three feet outward from a perpendicular dropped from the ends of the ridge. Thus it would reflect heat and light into the tent’s interior and there would be no detraction from the tent’s basic simplicity. In 1926 I designed a small tent in accordance with Sheldon’s suggestion and asked Dave Abercrombie to make it for me. It weighed just 6 1/2 pounds, and after these many years of use this tent is a good as new-barring a few spark holes-and I cannot think of a better shelter for a man who does his own camp work and loves the outdoors.

It is clear from the above that the original idea for this tent goes further back than Whelen’s 1926 version. It is obvious that Sheldon had already thought out the design and someone, most likely Sheldon, had the tent made prior to Whelen ever hearing about it. When I first discussed the photos I had discovered with Steve Watts, and before I had done any of this research, he argued for independent invention. I did not agree, based on the fact that the Whelen lean-to was too much like Sheldon’s tent. However, in looking back, I think Steve may have been onto something. Whelen designed his tent based on Sheldon’s suggestions and instructions and had it made in 1926, but I don’t think Whelen ever saw the tent pictured in the 1908 Sheldon photograph. I believe Whelen designed his tent based on Sheldon’s descriptions and suggestions alone. This would explain him saying (and rightfully so) that he “thought out” the design. I don’t think Colonel Whelen ever lied or try to hide anything. After all, in the passage above, he gives Sheldon full credit in print for giving him the ideas for his tent.

However, what we know today as the Whelen tent is a wonderful tent all its own. It owes its heritage to Sheldon, but ultimately the credit belongs to Whelen. Whelen made critical contributions to the final design of this tent, differentiating it from anything that existed before, including the Sheldon tent. He widened the center panel from what is pictured in the 1908 Sheldon photograph so that there is more room inside to sleep. With Sheldon’s tent, the side wings had to be spread when pitched so that there was enough room to stretch out. With the tent having to be pitched parallel to the wind to keep smoke and weather away from the sleeper, the splayed wings could be a problem. Whelen’s wider back panel added the option of bringing in the side wings to protect against blowing rain or snow (see Watts, In Praise of the Whelen Lean-To). Whelen also slightly reduced the height of the tent, making it even more resistant to rain and snow blowing in. This improved the tent’s ability to keep the warmth from the fire close to the sleeper. Finally, the material used was Green Egyptian cotton, making it rugged and less visible in the woods. These significant design changes coupled with the fact that Whelen probably spent more time than anyone else in the tent, justifies this tent being called the Whelen Lean-to. Whelen himself never referred to it as such until it was marketed under that name; he too, was simply seeking practicality. However, because the final design is Whelen’s, because he wrote extensively about it and because of his vast experience camping in it, it will always be known by that name, and it should be. If Whelen had not done these things, this unique and nearly perfect tent design would almost certainly have been lost to obscurity.

Author Biography:

Tom Ray, 53, grew up on a small farm near Lockhart, South Carolina. His youth was spent hunting, fishing, camping and trapping in and around the Broad River Basin and Sumter National Forest. As a result, he developed a lifelong interest in history, aboriginal studies, survival, primitive arts and frontier life. Early teachers were his older brother James and his Uncle, Grover Pinkney “Pink” Scott. For the last sixteen years, he has studied with Steve Watts at the Schiele Museum of Natural History. Another very important teacher is Errett Callahan. Other teachers and influences include David Wescott, Mel Deweese, Mors Kochanski and Dave Holladay. For the past 28 years, Tom has worked in private, public and technology education. He has taught numerous primitive skills classes and has presented a multitude of interpretive programs to a wide audience. His works have been published in the Bulletin of Primitive Technology, American Frontiersman and MasterWoodsman.com. He and his wife Claudia reside in Rock Hill, SC.

9 Responses to Origins of the Whelen Lean-To by Thomas Ray